Swaziland Country Summary

T: Higher Risk

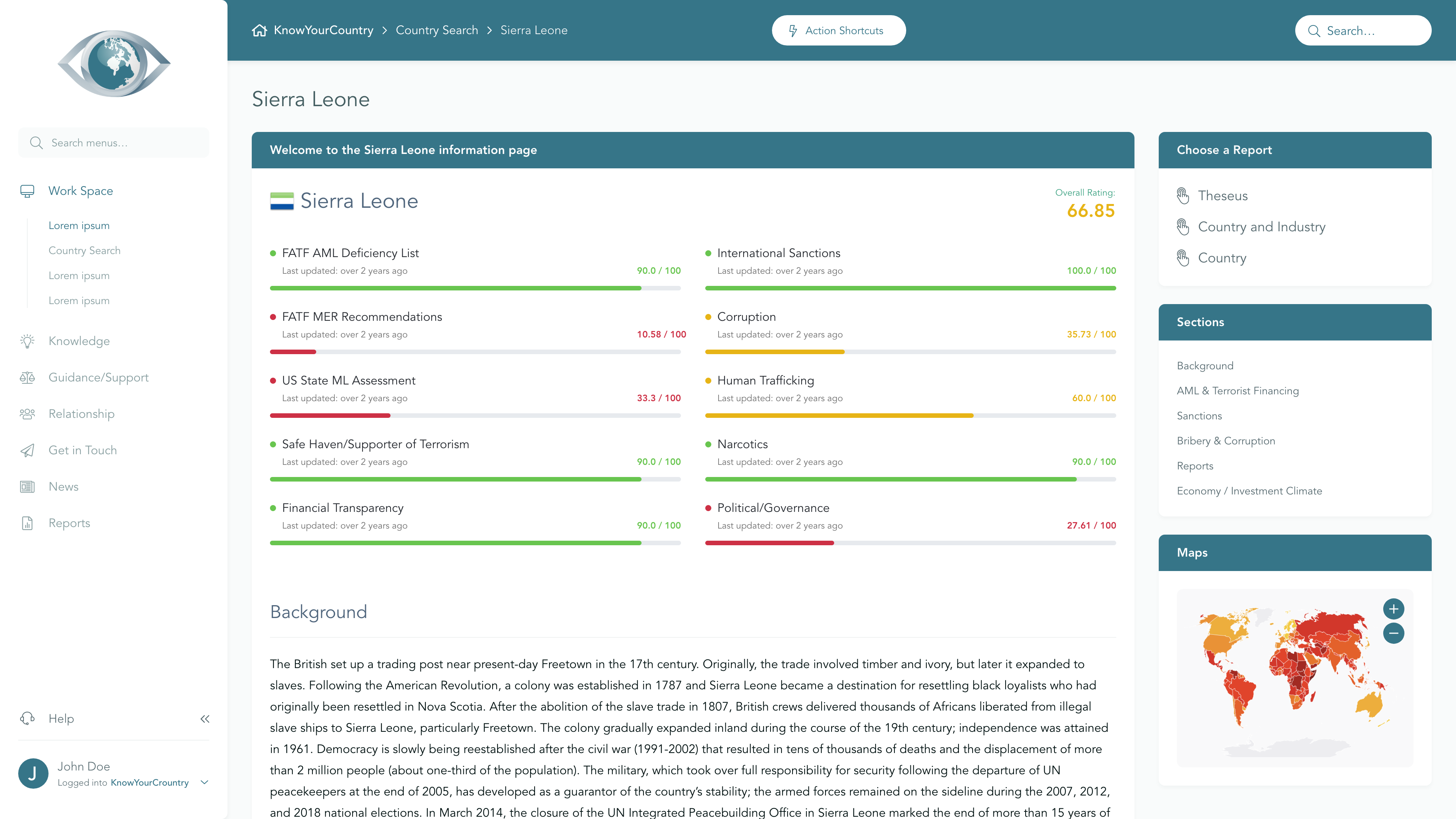

View full Ratings TableSanctions

No

FATF AML Deficient List

No

Terrorism

Corruption

US State ML Assessment

Criminal Markets (GI Index)

EU Tax Blacklist

Offshore Finance Center

Please note that although the below Summary will give a general outline of the AML risks associated with the jurisdiction, if you are a Regulated entity then you may need to demonstrate that your Jurisdictional AML risk assessment has included a full assessment of the risk elements that have been identified as underpinning overall Country AML risk. To satisfy these requirements, we would recommend that you use our Subscription area.

If you would like a demo of our Subscription area, please reserve a day/time that suits you best using this link, or you may Contact Us for further information.

Anti Money Laundering

FATF status

Swaziland is not on the FATF List of Countries that have been identified as having strategic AML deficiencies

Compliance with FATF Recommendations

The latest follow-up Mutual Evaluation Report relating to the implementation of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards in Eswatini (Swaziland) was undertaken in 2017 (original Mutual Evaluation done in 2011). According to the follow-up Evaluation, Eswatini was deemed Compliant for 1 and Largely Compliant for 0 of the FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations. It was Partially Compliant or Non-Compliant for 5 of the 6 of the Core Recommendations.

Key Findings from latest Mutual Evaluation Report (2011)

This mutual evaluation report summarises the anti-money laundering and combating of financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) measures in the Kingdom of Swaziland as observed during the onsite visit which took place on 15 – 26 February 2010 and two months thereafter. The report describes and analyses the measures in place and provides recommendations on how certain aspects of the AML/CFT system could be strengthened. It also sets out the levels of compliance obtained by the Kingdom of Swaziland with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) 40 Recommendations on money laundering and 9 Special Recommendation on terrorist financing, (See the attached table on the Ratings of Compliance with the FATF Recommendations). The Kingdom of Swaziland is a small landlocked developing country which is bordered on the north, west and south by the Republic of South Africa and on the east by the Republic of Mozambique. It has a small-export oriented diversified economy which is closely linked to the South African economy. The country is part of a monetary union with the Republic of Namibia, the Republic of South Africa and the Kingdom of Lesotho. The South African currency (the Rand) circulates freely on par with these countries’ national currencies within the union.

The financial sector in the Kingdom of Swaziland is small and dominated by subsidiaries of South African financial institutions. The dominant financial activity is commercial banking in which three of the four banks are subsidiaries of South African banks. The economy is predominantly cash-based. In order to reduce reliance on cash transactions, the Government of Swaziland in partnership with the banking sector is putting in place policy framework and infrastructure to promote access to financial services especially by low income earners.

The small size and proximity of the country to major cities in Mozambique and South Africa makes it a strategic transit country for illegal operations into these countries and Southern Africa at large. The major generators of proceeds include trafficking in human beings and drugs, counterfeiting of goods and currency, fraudulent cross- border bank transfers, tax and customs evasion, forgery, and theft. Proceeds generated through corrupt activities are also a major concern. As a result of the geographical location and economic profile of the country, the major crimes generating proceeds have manifestations of organised cross-border operations with the illicit funds invested within the monetary union, also known as the Common Monetary Area (CMA).The Kingdom of Swaziland is committed to addressing these challenges through various initiatives such as the promotion of law enforcement coordination and cooperation within and outside of the country, setting up of institutions to promote good governance and transparency in both public and private sector spheres. As for risk, money laundering is considered to be higher than terrorist financing and the authorities expect the latter to remain low for the foreseeable future.

Although the Kingdom of Swaziland started implementing AML measures in 2001 and later financing of terrorism in 2008, the development of these measures remain at infancy stage owing mainly to inadequate structures and resources to drive the process. The country is however making significant efforts to develop appropriate structures through changes to the national AML/CFT framework.

US Department of State Money Laundering assessment (INCSR)

Swaziland was deemed a ‘Monitored’ Jurisdiction by the US Department of State 2016 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR).

Key Findings from the report are as follows: -

The Kingdom of Swaziland is not considered a regional financial center. The financial sector in the Kingdom is small and dominated by subsidiaries of South African financial institutions. The small size of the country, the limited capacity of its police and financial regulators, and its proximity to major cities in Mozambique and South Africa make it a transit country for illegal operations in those countries and, to some extent, for the rest of the southern African region.

Large sums of money are moved via cross-border transactions involving banks, casinos, investment companies, motor vehicle dealers, and savings and credit cooperatives. Proceeds from the sale or trade of marijuana, a large illicit export, are laundered in Swaziland. Income from public corruption, particularly in public procurement, is also laundered in Swaziland. Cash gained from illegal activities is sometimes used to buy commercial goods and to build houses on non-titled land.

There is a significant black market for smuggled consumer goods, such as cigarettes, liquor, and pirated CDs and DVDs, transited across the porous borders of Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland. There is a general belief that trade-based money laundering and value transfer exists in Swaziland. Some traders transact in cash only and not through banks. Human trafficking is widespread. Swazi officials believe the Kingdom to be at little risk of terrorism financing.

The Common Monetary Area provides a free flow of funds among South Africa, Swaziland, Lesotho, and Namibia, with no exchange controls. Cash smuggling reports are informally shared on the basis of reciprocity among the relevant host government agencies.

DO FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ENGAGE IN CURRENCY TRANSACTIONS RELATED TO INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS TRAFFICKING THAT INCLUDE SIGNIFICANT AMOUNTS OF US CURRENCY; CURRENCY DERIVED FROM ILLEGAL SALES IN THE U.S.; OR ILLEGAL DRUG SALES THAT OTHERWISE SIGNIFICANTLY AFFECT THE U.S.: NO

CRIMINALIZATION OF MONEY LAUNDERING:

“All serious crimes” approach or “list” approach to predicate crimes: List approach

Are legal persons covered: criminally: YES civilly: YES

KNOW-YOUR-CUSTOMER (KYC) RULES:

Enhanced due diligence procedures for PEPs: Foreign: YES Domestic: YES KYC covered entities: Banks; asset managers; securities brokers and dealers; insurance agents and companies; currency brokers and exchanges; auditors, accountants, lawyers, and real estate agents; gaming entities and lotteries; and motor vehicle dealers

REPORTING REQUIREMENTS:

Number of STRs received and time frame: 50 in 2015

Number of CTRs received and time frame: Not applicable

STR covered entities: Banks; asset managers; securities brokers and dealers; insurance agents and companies; currency brokers and exchanges; auditors, accountants, lawyers, and real estate agents; gaming entities and lotteries; and motor vehicle dealers

MONEY LAUNDERING CRIMINAL PROSECUTIONS/CONVICTIONS:

Prosecutions: 3 in 2015

Convictions: 3 in 2015

RECORDS EXCHANGE MECHANISM:

With U.S.: MLAT: NO Other mechanism: NO

With other governments/jurisdictions: YES

Swaziland is a member of the Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG), a FATF-style regional body.

ENFORCEMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES AND COMMENTS:

Swaziland has taken several steps to establish an AML/CFT regime. In July 2015, the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) became an independent body governed by a board of directors. In order to demonstrate its autonomy, the FIU moved to its own office space. The FIU continues to expand; currently, it is recruiting staff and plans to hire 23 people. The positions include information technology specialists, finance, human resources, and compliance officers, as well as analysts. The new hires are expected to start in January 2016. ESAAMLG will assist with training the newly recruited FIU staff.

Implementation of cash transaction limits that require reporting to the FIU is ongoing. In addition, the AML task force supports a change in the law to require the reporting of cross- border movements of cash. The FIU has already set up two control points to monitor this reporting, one at the airport and another at the Oshoek border post with South Africa. Border posts with Mozambique are fairly well controlled.

The government has not yet passed the legislation necessary to amend the Money Laundering Act in order to make it compatible with the regulations already in place.

On September 3, 2015, Swaziland launched a Western Union international money transfer service in collaboration with Interchange, a leading foreign exchange service provider in the country.

The Royal Swaziland Police Service (RSPS) and the Kingdom’s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) are the two main law enforcement agencies charged with investigating money laundering offenses. The Swaziland Revenue Authority (SRA) is involved in the reporting and investigation of certain financial crimes. The RSPS is charged with investigating terrorism financing offenses. Significant weaknesses exist in the capacity to investigate and collect evidence for money laundering crimes, which results in prosecutors’ inability to pursue a case. According to Swazi officials, RSPS officers require additional training and capacity to be adequately prepared to investigate both money laundering and terrorism financing cases. Reports of money laundering cases are increasing, but some cases take a long time or do not make it to court because of a lack of resources.

The government should take steps to fully implement the requirements of UNSCRs 1267 and 1373, increase the capacity of police and investigative agencies to improve the effectiveness of money laundering investigations and prosecutions, and work to improve the production and reporting of relevant AML/CFT statistics. Swaziland should continue to develop cooperation among the RSPS, SRA, and the FIU to increase the number of successful prosecutions.

Sanctions

There are no international sanctions currently in force against this country.

Criminality

Rating (100-Good / 0-Bad)

Transparency International Corruption Index 33

World Governance Indicator – Control of Corruption 35

US State Department

The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government does not implement the law effectively. Officials sometimes engage in corrupt practices with impunity. Corruption continues to be a problem, most often involving personal relationships and bribes being used to secure government contracts on large capital projects.

The Prevention of Corruption Act and the Swaziland Public Procurement Act are the two laws that combat corruption by all persons, including public officials. The Public Procurement Act prohibits public sector workers and politicians from supplying the government with goods or services; however, this prohibition does not extend to family members of officials. The Eswatini Public Procurement Agency (ESPPRA) conducted capacity building exercises nationwide with both public and private companies to increase knowledge and encourage adoption of universally practiced purchasing systems. According to Section 27 of the Public Procurement Regulations, suppliers are prohibited from offering gifts or hospitality, directly or indirectly, to staff of a procuring entity, members of the tender board, and members of the ESPPRA. While avoiding conflict of interest and establishing codes of conduct are policies that are encouraged, they are not effectively enforced. Some companies use internal controls and audit compliance programs to try to track and prevent bribery.

Eswatini is a signatory to the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and Related Offenses and the SADC Protocol against Corruption. Eswatini has signed and ratified the UN Anticorruption Convention, but it is not party to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.

The Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) is legally allowed to investigate corruption, and does so. The ACC does not provide protection to NGOs involved in investigating corruption. Given the Commission’s current capacity, “government procurement” is the most likely area to find corruption in Eswatini. The global competitiveness report ranks Swaziland 79 of 140 countries on incidence of corruption. Transparency International reports Eswatini as the 14th least corrupt country in Africa

Though no US firms have cited corruption, the 2015 Africa Competitiveness report found that 12.8% of business owners saw corruption as a hurdle to doing business in Eswatini, impacting profits, contracts, and investment decisions for their companies. There is a public perception of corruption in the executive and legislative branches of government and a consensus that the government does little to combat it. There have been credible reports that a person’s relationship with government officials influenced the awarding of government contracts; the appointment, employment, and promotion of officials; recruitment into the security services; and school admissions. Authorities rarely took action on reported incidents of nepotism.

Economy

A small, landlocked kingdom, Swaziland ("Eswatini") is bordered in the north, west and south by the Republic of South Africa and by Mozambique in the east. Eswatini depends on South Africa for a majority of its exports and imports. Eswatini's currency is pegged to the South African rand, effectively relinquishing Eswatini's monetary policy to South Africa. The government is dependent on customs duties from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) for almost half of its revenue. Eswatini is a lower middle income country. As of 2017, more than one-quarter of the adult population was infected by HIV/AIDS; Eswatini has the world’s highest HIV prevalence rate.

The manufacturing sector diversified in the 1980s and 1990s, but manufacturing has grown little in the last decade. Sugar and soft drink concentrate are the largest foreign exchange earners, although a drought in 2015-16 decreased sugar production and exports. Overgrazing, soil depletion, drought, and floods are persistent problems. Mining has declined in importance in recent years. Coal, gold, diamond, and quarry stone mines are small scale, and the only iron ore mine closed in 2014. With an estimated 28% unemployment rate, Eswatini's need to increase the number and size of small and medium enterprises and to attract foreign direct investment is acute.

Eswatini's national development strategy, which expires in 2022, prioritizes increases in infrastructure, agriculture production, and economic diversification, while aiming to reduce poverty and government spending. Eswatini's revenue from SACU receipts are likely to continue to decline as South Africa pushes for a new distribution scheme, making it harder for the government to maintain fiscal balance without introducing new sources of revenue.

Agriculture - products:

sugarcane, corn, cotton, citrus, pineapples, cattle, goats

Industries:

soft drink concentrates, coal, forestry, sugar processing, textiles, and apparel

Exports - commodities:

soft drink concentrates, sugar, timber, cotton yarn, refrigerators, citrus, and canned fruit

Exports - partners (2017):

| Trade (US$ Mil) | Partner share (%) | |

| South Africa | 1,250 | 69.36 |

| Kenya | 106 | 5.91 |

| Nigeria | 84 | 4.67 |

| Mozambique | 59 | 3.3 |

| Tanzania | 35 | 1.96 |

Imports - commodities:

motor vehicles, machinery, transport equipment, foodstuffs, petroleum products, chemicals

Imports - partners (2017):

| Trade (US$ Mil) | Partner share (%) | |

| South Africa | 1,248 | 77.63 |

| China | 106 | 6.58 |

| India | 36 | 2.24 |

| United States | 29 | 1.78 |

| Singapore | 19 | 1.2 |

The above information relating to exports/imports is provided by the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), a collaboration between the World Bank and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

To access WITS for more detailed information into trade on a product by product / country by country basis, please go to: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/WLD/Year/2018/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/WLD/Product/all-groups

Investment Climate

Executive Summary

Eswatini is a landlocked kingdom in Southern Africa. Although the official government policy is to encourage foreign investment as a means to drive economic growth, the pace of reforming investment policies is slow. Following a September 2018 general election, a new Prime Minister and cabinet (including several former CEOs and others with significant private sector experience) took office and assumed the task of turning around Eswatini’s economy. The Eswatini Investment Promotion Authority (EIPA) advocates for foreign investors and facilitates regulatory approval but lacks the political clout to achieve its core functions. Recent positive developments include the country’s January 2018 reinstatement under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the enactment of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act and updated intellectual property legislation, and improvements in the 2019 Ease of Doing Business rankings.

The Swati government has prioritized the energy sector, particularly renewable energy, and developed a Grid Code and Renewable Energy and Independent Power Producer (RE&IPP) Policy to create a transparent regulatory regime and attract investment. Eswatini generally imports 80 percent of its power from South Africa and Mozambique. With both South Africa and Mozambique experiencing electricity shortages, Eswatini is working to increase its own energy generation using renewable sources. To that end, the country has launched a small handful of new photovoltaic projects. Information, Communications and Technology (ICT) is also an emerging sector, which Eswatini has tried to support through initiatives such as e-governance and the Royal Science and Technology Park. The digital migration program of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) presents ICT opportunities in the country.

Incentives to invest in Eswatini include repatriation of profits, fully serviced industrial sites, purpose-built factory shells at competitive rates, and duty exemptions on raw materials for manufacture of goods to be exported outside the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Financial incentives for all investors include tax allowances and deductions for new enterprises, including a 10-year exemption from withholding tax on dividends and a low corporate tax rate of 10 percent for approved investment projects. New investors also enjoy duty-free import of machinery and equipment. SEZ investors may benefit from a 20-year exemption from all corporate taxation (followed by taxation at 5 percent); full refunds of customs duties, value-added tax, and other taxes payable on goods purchased for use as raw material, equipment, machinery, and manufacturing; unrestricted repatriation of profits; and full exemption from foreign exchange controls for all operations conducted within the SEZ.

Royal family involvement in the mining sector has discouraged potential investors in that sector. Eswatini’s land tenure system, where the majority of rural land is “held in trust for the Swati nation,” has discouraged long-term investment in commercial real estate and agriculture.

Recent legislative reforms such as the enactment of the new Public Order Act and Sexual Offenses and Domestic Violence Act have meaningfully improved the country’s legal framework. After requalifying as an AGOA beneficiary in January 2018, Eswatini turned its attention to trying to qualify for Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) support. To advance these efforts, the country has launched an effort to improve its relatively poor rankings on MCC indicators such as political rights, civil liberties, and business start-up.

| Measure | Year | Index/Rank | Website Address |

| TI Corruption Perceptions Index | 2019 | 113 of 180 | http://www.transparency.org/research/cpi/overview |

| World Bank’s Doing Business Report | 2019 | 121 of 190 | http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings |

| Global Innovation Index | 2019 | Eswatini not included | https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/analysis-indicator |

| U.S. FDI in partner country ($M USD, historical stock positions) | N/A | N/A | https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/ |

| World Bank GNI per capita | 2018 | $3,930 | http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD |

Openness To, and Restrictions Upon, Foreign Investment

Policies Towards Foreign Direct Investment

The Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini (GKoE) regards foreign direct investment (FDI) as one of the five pillars of its Sustainable Development and Inclusive Growth (SDIG) Program, and a means to drive the country’s economic growth, obtain access to foreign markets for its exports, and improve international competitiveness. While the government has strongly encouraged foreign investment over the past 15 years, it only recently adopted a formal strategy for achieving measurable progress. Eswatini does not have a unified policy on investment. Instead, individual ministries have their own investment facilitation policies, which include policies on Small and Medium Enterprises (SME), agriculture, energy, transportation, mining, education, and telecommunications. Calls for more concerted action on these policies have intensified in the last few years as Eswatini has suffered from drought, fiscal challenges, and general economic recession.

The Swati constitution states, generally, that non-citizens and/or companies with a majority of non-citizen shareholders may not own land unless they were vested in their ownership rights before the constitution entered into force in 2006. On the other hand, the constitution’s general prohibition “may not be used to undermine or frustrate an existing or new legitimate business undertaking of which land is a significant factor or base.” Furthermore, non-citizens and non-citizen majority-owned companies may hold long-term (up to 99 years) leases on Title and Swati Nation Land. Besides land ownership laws, there are no laws that discriminate against foreign investors. In 2019, the government listed some of its title deed land to make it available for long-term leasing for commercial purposes.

In practice, most successful foreign investors associate local partners to navigate Eswatini’s complex bureaucracy. Most of the country’s land is Swati Nation Land held by the king “in trust for the Swati Nation” and cannot be purchased by foreign investors. Foreign investors that require significant land for their enterprise must engage the Land Management Board to negotiate long-term leases.

The Eswatini Investment Promotion Authority (EIPA) is the state-owned enterprise (SOE) charged with designing and implementing strategies for attracting desired foreign investors.

Eswatini’s Investment Policy and policies that support the business environment are online at https://investeswatini.org.sz/legal-and-regulatory-framework/ (EIPA is currently functional and helpful, but it is not yet a one-stop-shop for foreign investors. EIPA services include: – Attract and promote local and foreign direct investments

- Attract and promote local and foreign direct investments

- Identify and disseminate trade and investment opportunities

- Provide investor facilitation and aftercare services

- Promote internal and external trade

- Undertake research and policy analysis

- Facilitate company registration and business licenses/permits

- Facilitate work permits and visas for investors

- Provide a one stop shop information and support facility for businesses

- Export product development

- Facilitation of participation in external trade fairs

- BuyerSeller Missions

The GKoE continues its attempts to improve the ease of doing business in the country through the Investor Roadmap Unit (IRU). The IRU engages with businesses and government to review and report on the progress and implementation of the investor roadmap reforms.

EIPA has an aftercare division for purposes of investment retention, which is a direct avenue for investors to communicate concerns they may have. Most investors who stay beyond the initial period during which the GKoE offers investment incentives have opted to remain long-term.

Limits on Foreign Control and Right to Private Ownership and Establishment

Both foreign and domestic private entities have a right to establish businesses and acquire and dispose of interest in business enterprises. Foreign investors own several of Eswatini’s largest private businesses, either fully or with minority participation by Swati institutions.

There are no general limits on foreign ownership and control of companies, which can be 100 percent foreign owned and controlled. The only exceptions on foreign ownership and control are in the mining sector and in relation to land ownership. The Mines and Minerals Act of 2011 requires that the King (in trust for the Swati Nation) be granted a 25-percent equity stake in all mining ventures, with another 25 percent equity stake granted to the GKoE. There are also sector-specific trade exclusions that prohibit foreign control, which include business dealings in firearms, radioactive material, explosives, hazardous waste, and security printing.

Foreign investments are screened only through standard background and credit checks. Under the Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism (Prevention) Act of 2011, investors must submit certain documents including proof of residence and source of income for deposits. EIPA also conducts general screening of FDI monies through credit bureau checks and Interpol. This screening is not a barrier to investing in Eswatini. There are no discriminatory mechanisms applied against US foreign direct investors.

Other Investment Policy Reviews

In 2015, the WTO performed a Trade Policy Review of the Southern African Customs Union, which included Namibia, Botswana, Eswatini, South Africa, and Lesotho. In 2016, the Trade facilitation agreement was ratified Eswatini’s portion of that review is available online: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/archive_e/country_arc_e.htm?country1=SWZ

Business Facilitation

Eswatini does not have a single overarching business facilitation policy. Policies that address business facilitation are spread across the spectrum of relevant ministries. The IRMU is the public entity responsible for the review and monitoring of business environment reforms. EIPA facilitates foreign and domestic investment opportunities and has a fairly modern, up-to-date website: https://investeswatini.org.sz/. Certain GKoE application forms are available online at the EIPA website. Recent developments in the business facilitation space include the online registration of companies via the link www.online.gov.sz. However, some of the steps (payment of statutory fees and registration fee) still must be completed offline. According to the Doing Business Report, the process of registering a company in Eswatini takes approximately 10 days. In practice, the process can take much longer for foreign investors.

The main organization representing the private sector is Business Eswatini (www.business-eswatini.co.sz), which represents more than 80 percent of large businesses in Eswatini, works on a wide range of issues of interest to the private sector, and seeks to build partnerships with the government to promote commercial development. Through Business Eswatini, the private sector is represented in a number of national working committees, including the National Trade Negotiations Team (NTNT).

Financial Sector

Capital Markets and Portfolio Investment

Eswatini’s capital markets are closely tied to those of South Africa and operate under conditions generally similar to the conditions in that market. In 2010, the GKoE passed the Securities Act to strengthen the regulation of portfolio investments. The Act was primarily intended to facilitate and develop an orderly, fair, and efficient capital market in the country.

Eswatini has a small stock exchange with only a handful of companies currently trading. In 2010, the Financial Services Regulatory Authority (FSRA) was established. This institution governs non-bank financial institutions including capital markets, insurance firms, retirement funds, building societies, micro-finance institutions, and savings and credit cooperatives. The royal wealth fund and national pension fund invest in the private equity market, but otherwise there are few professional investors.

Existing policies neither inhibit nor facilitate the free flow of financial resources. The demand is simply not present. The Central Bank respects International Monetary Fund (IMF) Article VIII. Credit is allocated on market terms. Foreign investors are able to get credit and equity from the local market. A variety of credit instruments are available to the private sector including Central Bank of Eswatini loan guarantees for the export markets and for small businesses.

Money and Banking System

54 percent of the Swati adult population is banked. Despite a slow rate of economic growth, the Swati banking sector remains stable and financially sound. Asset quality improved as the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to gross loans, moved from 8.2 percent in 2017 to 7.7 percent in 2018.

54 percent of the Swati adult population is banked. Despite a slow rate of economic growth, the Swati banking sector remains stable and financially sound. Asset quality improved as the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to gross loans, moved from 8.2 percent in 2017 to 7.7 percent in 2018.

The estimated total assets for the country’s banks is estimated at E19.4 billion (USD 1.4 billion) as at June 2018, up from E17.9 billion (USD 1.3 billion) in March 2017. Eswatini has a central bank system. Eswatini’s banks are primarily subsidiaries of South African banks. Standard Bank is the largest bank by capital assets and employs about 400 workers. In 2018, the Central Bank of Eswatini under the Financial Institutions Act of 2005 awarded a new commercial banking license to Farmer’s Bank.

Eswatini’s financial sector is liberalized and allows foreign banks or branches to operate under the supervision of the Central Bank’s laws and regulations (http://www.centralbank.org.sz/financialregulation/banksupervision/index.php). Foreigners may establish a bank account in Eswatini if they have residency in one of the CMA countries (Eswatini, South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia).

There have been no bank closures or banks in jeopardy in the last three years. Hostile takeovers are uncommon.

Foreign Exchange and Remittances

Foreign Exchange

There are no limitations on the inflow or outflow of funds for remittances. Dividends derived from current trading profits are freely transferable on submission of appropriate documentation to the Central Bank, subject to provision for the non-resident shareholder tax of 15 percent. Local credit facilities may not be utilized for paying dividends. Eswatini is part of the Common Monetary Area (CMA), which also includes South Africa, Namibia, and Lesotho. All capital transfers into Eswatini from outside the CMA require prior approval of the Central Bank to avoid problems in the subsequent repatriation of interest, dividends, profits, and other income accrued. Otherwise, there are no restrictions placed on the transfers.

Eswatini mainly deals with three international currencies: the U.S. Dollar, the Euro, and the British Pound. The Swati Lilangeni is pegged 1:1 to the South African Rand, which is accepted as legal tender throughout Eswatini. To obtain foreign currency other than Rand, one must apply through an authorized dealer, and a resident who acquires foreign currency must sell it to an authorized dealer for the local currency within ninety days. No person is permitted to hold or deal in foreign currency other than authorized dealers, namely, First National Bank (FNB), Nedbank, Standard Bank, or Swazi Bank.

Because the Lilangeni is pegged to the Rand, its value is determined by the monetary policy of the CMA, which is heavily influenced by the South African Reserve Bank.

Remittance Policies

There have been no recent changes to investment remittance policies. There are no specified time limitations on remittances. Once documentation is complete (e.g., latest company financial statements) and relevant taxes paid, SWIFT transfers require an average of one week, and other electronic transfers can take less than a week (SWIPPS offers real-time transactions).

SWIPSS, Eswatini’s Real Time Gross Settlement System, is an advanced interbank electronic payment system that facilitates the efficient, safe, secure and real-time transmission of high-value funds in the banking sector. Direct access to SWIPSS is limited to only the four commercial banks, and these banks act as intermediaries for other financial institutions.

As part of the government policy to attract foreign investment, dividends derived from current trading profits are freely transferable on submission of documentation (including latest annual financial statements of the company concerned) subject to provision for non-resident shareholders tax. The Eswatini government does not issue dollar-denominated bonds. Otherwise, there are no limitations on the inflow and outflow of funds for remittances of profits or revenue.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

In 1968, the late King Sobhuza II created a Royal Charter that governs the Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) in Eswatini, Tibiyo TakaNgwane. This fund is not subject to government or parliamentary oversight and does not provide information on assets or financial performance to the public. Tibiyo TakaNgwane publishes an annual report with financials, but it is not required by law to do so as it is not registered under the Companies Act of 1912. The annual reports are not made public or submitted to any other state organ for debate or review. The SWF obtains independent audits at the discretion of its Board of Directors.

Tibiyo TakaNgwane states in its objectives that it supports the government in fostering economic independence and self-sufficiency. It widely invests in the economy and holds shares in most major industries, e.g., sugar, real estate, beverages, dairy, hotels, and transportation. For its social responsibility practices, it provides some scholarships to students. The SWF and the government co-invest to exercise majority control in many instances. Tibiyo TakaNgwane invests entirely in the local economy and local subsidiaries of foreign companies. It has shares in a number of private companies. Sometimes foreign companies can form partnerships with Tibiyo, especially if the foreign company wants to raise capital and can manage the project on its own.

State-Owned Enterprises

Eswatini has over 30 SOEs, which are active in agribusiness, information and communication, energy, automotive and ground transportation, health, housing, travel and tourism, building education, business development, finance, environment, and publishing, media, and entertainment.

The Swati government defines SOEs as private enterprises, separated into two categories. Category A represents SOEs that are wholly owned by government. Category B represents SOEs in which government has a minority interest, or which monitor other financial institutions or a local government authority. These categories are further broken down into profit-making SOEs with a social responsibility focus, those that are profit-making and developmental, those that are regulatory, and those that are regulatory but developmental. SOEs purchase and supply goods and services to and from the private sector including foreign firms. Those in which government is a minority shareholder are subject to the same tax burden and tax rebate policies as the private sector. The Public Enterprise Act governs SOEs. The Boards of the respective SOEs review their budgets before tabling them to the relevant line ministry, which, in turn, tables them to Parliament for scrutiny by the Public Accounts Committee. The Ministry of Finance’s Public Enterprise Unit (PEU) maintains a published list of SOEs, available on request from the PEU. SOEs do not receive non-market based advantages from government.

Eswatini SOEs generally conform to the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance for SOEs. Senior managers of SOEs report to the board and, in turn, the board reports to a line minister. The minister then works with the Standing Committee on Public Enterprise (SCOPE), which is composed of cabinet ministers. SOEs are governed by the Public Enterprises Act, which requires audits of the SOEs and public annual reports. Government is not involved in the day-to-day management of SOEs. Boards of SOEs exercise their independence and responsibility. The Public Enterprise Unit provides regular monitoring of SOEs. The line minister of the SOE appoints the board and, in some cases, the appointments are politically motivated. In some cases, the king appoints his own representative as well. Generally, court processes are nondiscriminatory in relation to SOEs.

A published list of SOEs can be found on: http://www.gov.sz/index.php/component/content/article/141-test/1995-swaziland-enterprise-parastatals?Itemid=799

Eswatini SOEs operate primarily in the domestic market.

Privatization Program

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has long advised the Eswatini government to privatize SOEs, particularly in the telecommunications sector and the electricity sector. In response, the government has passed several laws, and privatization efforts have begun to advance. The past two years have seen the launch of several private telecommunications companies such as Swazi Mobile, which has lowered prices and improved mobile and data offerings in the country.

Sectors and timelines have not been prioritized for future privatization, although it is likely that some SOEs following the public launch of the Revised National Development Strategy.

The government is working to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign electricity by promoting renewable energy production. Eswatini imports the bulk of its electricity from South Africa and Mozambique, reaching 100 percent importation during a recent drought, since domestic production comes predominantly from hydropower. With assistance from USAID’s Southern Africa Energy Program (SAEP), the government has developed a National Grid Code and a Renewable Energy and Independent Power Producer (RE&IPP) Policy to provide a framework for the sector and incentivize investors. SAEP is currently providing technical assistance on a 10-megawatt photovoltaic projects that are projected to integrate into the grid by late 2020.

Political and Security Environment

There are few incidents of politically motivated violence. In 2017, the Swati government enacted a new Public Order Act and amendments to the Suppression of Terrorism Act that have dramatically reduced restrictions on assembly, association, and expression. Through April 2020, the GKoE has done a fairly good job of honoring the newly expanded legal freedoms. There are no examples from the past ten years of damage to projects or installations. Overall, Eswatini has a long record of political stability with sporadic nonviolent protest; however, poor living and working conditions, widespread poverty, income inequality, and a large and growing youth population continue to yield a political environment conducive to unrest.

Investment Climate information provided by US State Department

Subscribe to

Professional Plus

- Unlimited Access to full Risk Reports

- Full Dataset Download

- API Access

- Virtual Asset Risk Assessments